The Horror Writers Association has asked its members to let people know that the new edition of On Writing Horror, edited by Mort Castle and the HWA, with chapters by Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, Harlan Ellison, Ramsay Campbell and others, is now available. So I have.

I haven't see the book yet, but I did find the previous edition useful.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Bitumen punk?

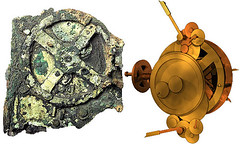

Yesterday I heard a piece on NPR about a curious device known as the Antikythera mechanism, a complex arrangement of iron and bronze gears discovered in 1900 by Greek sponge divers blown off course by a storm. The device has intrigued researchers since its discovery, and now a team of British, Greek and American scientists have announced that it is nothing less than an astronomical computer.

This is quite a sophisticated application of mechanical technology. Was the Antikythera mechanism the pinnacle of this technology, or did the Greeks push the boundaries ever further? Might accurate Greco orrerys be hiding in the wreckage of some other sunken ship as yet undiscovered? Some evidence suggest that the trade ship carrying the device originated in Rhodes, home of the famed ancient astronomer Hipparchus. The trade ship sank around 65 B.C., and researchers estimate the Antikythera mechanism was constructed sometime between 150-100 B.C. Since Hipparchus died around 120 B.C., the intriguing possibility that he was involved in its design is hard to avoid.

I have to wonder how long it will be now before someone publishes an alternate history in which Hipparchus is cast as a Charles Babbage figure, and the Antikythera mechanism a forerunner of some Hellenic difference engine incarnation. What's the over/under on that? Since the two devices are purely mechanical, it seems the technological gulf between the two devices isn't nearly as wide as the two millennia separating them might suggest. What advances in Greek metalworking would be necessary for them to begin to approximate the design of Babbage's polynomial function tabulator?

They concluded that the device contained 37 gears, about 30 of which still survive. It was originally housed in a wooden case slightly smaller than a shoebox.

Two dials on the front show the zodiac and a calendar of the days of the year that can be adjusted for leap years. Metal pointers show the positions in the zodiac of the sun, moon and five planets known in antiquity. Two spiral dials on the back show the cycles of the moon and predict eclipses.

The complicated meshing of the gears is a physical representation of the so-called Callippic and saros astronomical cycles. In the Callippic cycle, for example, the sun, moon and Earth return to the same relative orientations four times in 76 years minus one day.

The saros cycle predicts that, following a solar or lunar eclipse, a similar eclipse will occur 223 lunar months later.

By turning the gears with a hand crank, the user could select a specific day in the past or future and observe the positions of the heavenly objects on that day.

This is quite a sophisticated application of mechanical technology. Was the Antikythera mechanism the pinnacle of this technology, or did the Greeks push the boundaries ever further? Might accurate Greco orrerys be hiding in the wreckage of some other sunken ship as yet undiscovered? Some evidence suggest that the trade ship carrying the device originated in Rhodes, home of the famed ancient astronomer Hipparchus. The trade ship sank around 65 B.C., and researchers estimate the Antikythera mechanism was constructed sometime between 150-100 B.C. Since Hipparchus died around 120 B.C., the intriguing possibility that he was involved in its design is hard to avoid.

Dr. Charette noted that more than 1,000 years elapsed before instruments of such complexity are known to have re-emerged. A few artifacts and some Arabic texts suggest that simpler geared calendrical devices had existed, particularly in Baghdad around A.D. 900.

It seems clear, Dr. Charette said, that “much of the mind-boggling technological sophistication available in some parts of the Hellenistic and Greco-Roman world was simply not transmitted further,” adding, “The gear-wheel, in this case, had to be reinvented.”

I have to wonder how long it will be now before someone publishes an alternate history in which Hipparchus is cast as a Charles Babbage figure, and the Antikythera mechanism a forerunner of some Hellenic difference engine incarnation. What's the over/under on that? Since the two devices are purely mechanical, it seems the technological gulf between the two devices isn't nearly as wide as the two millennia separating them might suggest. What advances in Greek metalworking would be necessary for them to begin to approximate the design of Babbage's polynomial function tabulator?

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Pulp Dreams

Sometime in the late 80s, visiting a buddy in the Lower East Side, I heard about the sightings of Doc Savage in Alphabet City.

Sometime in the late 80s, visiting a buddy in the Lower East Side, I heard about the sightings of Doc Savage in Alphabet City.Not some Bohemian adventure that Lester Dent had failed to transcribe. Not some Philip Jose Farmer pulp hero retired to Sin City satirical homage.

No, this was the real thing, as in, "Dude, I was walking down to the coffee shop the other day and I saw *Doc Savage* headed for the train."

I was jealous. Later, I heard of other sightings, many of them second hand.

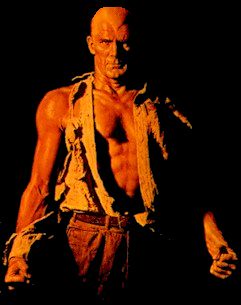

In a coffee shop last year I came across a Portland zine, Book Happy, which featured an article by Ken DeVries about "That Guy!" -- the craggy, frequently half-naked man whose image adorns a large number of genre paperbacks of the late 60s and early 70s.

I recognized that guy. He was Doc Savage. The Doc Savage of the Bantam paperbacks, the embodiment of the spirit of Men's Adventure circa 1973. The guy my buddies said they had seen walking the streets of Ed Koch's New York, albeit with the bronze bleached out from years of high mileage fighting the evildoers.

He was also the face of a hundred other pulp heroes and pop archetypes of masculinity. Nick Carter. The Avenger. The Spy With the Blue Kazoo. The President's Agent. The Professionals. The man getting the benefits of The Harrad Experiment. Desmond Morris' The Naked Ape. Dig around any section of the nearest run-down paperback exchange and you'll find him.

At my neighborhood comic shop last weekend I came across the new coffee table tome about illustrator James Bama, official psychic sculptor of my personal juvenile Zeitgeist.

A section of the book talks about the man who served in all these roles. Turns out, as I had earlier learned, it *was* all the same guy. Steve Holland, an actor (1950s Flash Gordon TV series, among other things) who became the most popular model for the pulp illustrators. He had the look. Not the steroid-fueled suburban gym look of the Boris Vallejo guys, not the fluid expressionist barbarian energy of the Frazetta guys, but the chiseled and grizzled creases of the dark side of the greatest generation, the guys who came into their looks by fighting actual wars and living off the grit of the mid-20th century. All Spillane, no Schwarzenegger.

A section of the book talks about the man who served in all these roles. Turns out, as I had earlier learned, it *was* all the same guy. Steve Holland, an actor (1950s Flash Gordon TV series, among other things) who became the most popular model for the pulp illustrators. He had the look. Not the steroid-fueled suburban gym look of the Boris Vallejo guys, not the fluid expressionist barbarian energy of the Frazetta guys, but the chiseled and grizzled creases of the dark side of the greatest generation, the guys who came into their looks by fighting actual wars and living off the grit of the mid-20th century. All Spillane, no Schwarzenegger. Turns out, according to Bama, the only thing Holland did to maintain his appearance was play a little urban handball against a concrete wall.

He was the archetypal representation of the uber-character of the entire meta-genre. Leathered face and gaunt musculature revealing everything you needed to know about the character. A face that had never looked at itself in a mirror, unless you count that blood-clouded puddle in the mud. Skin that had never been exposed to cathode rays or skin creams. A character of whom our coddled, stylized, self-observant post-Baby Boom protagonists can only ever be diluted shadows.

There's a Borgesian revelation when you realize this one guy was the illustrative embodiment of all these pulp heroes. I don't know if it matters, but I wish I'd run into him on Rivington Street back in 1988. Too bad he disappeared forever with the last gasps of the Cold War.

There's a Borgesian revelation when you realize this one guy was the illustrative embodiment of all these pulp heroes. I don't know if it matters, but I wish I'd run into him on Rivington Street back in 1988. Too bad he disappeared forever with the last gasps of the Cold War.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Zoran Živković

Zoran Živković was born in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia, in 1948. In 1973 he graduated from the Department of General Literature with the theory of literature, Faculty of Philology of the University of Belgrade; he received his master's degree in 1979 and his doctorate in 1982 from the same school. He lives in Belgrade, Serbia, with his wife Mia, their twin sons Uros and Andreja, and their four cats. He is the winner of the 1994 Milos Crnjanski Award for The Fourth Circle and the 2003 World Fantasy Award for The Library. His website can be found at www.zoranzivkovic.com.

Zoran Živković was born in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia, in 1948. In 1973 he graduated from the Department of General Literature with the theory of literature, Faculty of Philology of the University of Belgrade; he received his master's degree in 1979 and his doctorate in 1982 from the same school. He lives in Belgrade, Serbia, with his wife Mia, their twin sons Uros and Andreja, and their four cats. He is the winner of the 1994 Milos Crnjanski Award for The Fourth Circle and the 2003 World Fantasy Award for The Library. His website can be found at www.zoranzivkovic.com.

Jess Nevins

Well, let's see now...I'm 40, American, a Bostonian currently trapped in rural Texas, happily married to the best woman in the world for me, a university librarian, the author of books of annotations of Alan Moore's comics, the author of The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana, the author of the forthcoming The Encyclopedia of Pulp Heroes and The Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes, and the writer of one novel, desperately in need of revision. My website's at http://www.geocities.com/ratmmjess/.

Well, let's see now...I'm 40, American, a Bostonian currently trapped in rural Texas, happily married to the best woman in the world for me, a university librarian, the author of books of annotations of Alan Moore's comics, the author of The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana, the author of the forthcoming The Encyclopedia of Pulp Heroes and The Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes, and the writer of one novel, desperately in need of revision. My website's at http://www.geocities.com/ratmmjess/.

Alexis Glynn Latner

My novelettes and short stories have appeared in Analog, Amazing Stories, and the anthology Bending the Landscape: Horror, plus an upcoming story in the anthology Horrors Beyond II. My science fiction novel Hurricane Moon will be published by Pyr in July 2007. I'm currently the South/Central Regional Director for the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). I work at the Rice University Library, and besides writing speculative fiction, I do editing, write magazine articles about science, technology, and aviation, and teach creative writing. For fun and real-life adventure I'm a sailplane pilot in the Soaring Club of Houston. I also have a website at http://www.sff.net/people/alexis-latner/.

My novelettes and short stories have appeared in Analog, Amazing Stories, and the anthology Bending the Landscape: Horror, plus an upcoming story in the anthology Horrors Beyond II. My science fiction novel Hurricane Moon will be published by Pyr in July 2007. I'm currently the South/Central Regional Director for the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). I work at the Rice University Library, and besides writing speculative fiction, I do editing, write magazine articles about science, technology, and aviation, and teach creative writing. For fun and real-life adventure I'm a sailplane pilot in the Soaring Club of Houston. I also have a website at http://www.sff.net/people/alexis-latner/.

Chris N. Brown

Chris N. Brown (aka Chris Nakashima-Brown) writes fiction and criticism from his home in Austin, Texas. His work has been variously described as "slick, post-Gibsonian, and funny as hell, like Neal Stephenson meets Hunter S. Thompson" (Cory Doctorow), "JG Ballard with a Texas twang" (SF Site), "Borges in a pop culture blender" (Invisible Library), and "like a cross between Mark Leyner and William Gibson" (Boing Boing); he calls it "pulp fiction for smart people." A complete bibliography including links to work available online can be found on his website.

Chris N. Brown (aka Chris Nakashima-Brown) writes fiction and criticism from his home in Austin, Texas. His work has been variously described as "slick, post-Gibsonian, and funny as hell, like Neal Stephenson meets Hunter S. Thompson" (Cory Doctorow), "JG Ballard with a Texas twang" (SF Site), "Borges in a pop culture blender" (Invisible Library), and "like a cross between Mark Leyner and William Gibson" (Boing Boing); he calls it "pulp fiction for smart people." A complete bibliography including links to work available online can be found on his website.

Stephen Dedman

Stephen Dedman's bio

Stephen Dedman's bioI was born in 1959, and grew up (though many would dispute this) mostly in Western Australia. I escaped from most of that state's institutions of higher learning at one time or another, but was lured back in the 1990s, received my M.A., and am in the last throes of writing my Ph.D. thesis. I'm the author of the novels The Art of Arrow Cutting, Shadows Bite, Foreign Bodies and Shadowrun: A Fistful of Data, and more than 100 short stories; fiction editor for Borderlands magazine; part-time creative writing tutor and book reviewer; and book buyer for Fantastic Planet science fiction specialist bookshop. I've won an Aurealis Award and a Ditmar, and been nominated for a Bram Stoker Award, a British Science Fiction Association Award, a Seiun Award, a Spectrum Award, a Sidewise Award, and a sainthood.

I still live in Western Australia, with my wife Elaine (also a writer) and a finite number of cats. My bibliography can be seen at

http://stephen-dedman.livejournal.com/38569.html

Jayme Lynn Blaschke

Thanks for stopping by to check out my obligatory "Who is this guy?" post here at No Fear of the Future. In case you're wondering (and I'll be deeply traumatized if you're not) I'm Jayme Lynn Blaschke, a science fiction and fantasy writer as well as journalist and PR flack from Texas. If you're a science fiction fan from the U.K., there's half a chance you may have heard of me, as Interzone has published more short fiction of mine than anyone else, not to mention a dozen or so interviews I've conducted with sage and knowing genre types over the years. If you're not British, then the pickin's get a bit leaner. I've published a collection of 17 interviews through Bison Books titled, Voices of Vision: Creators of Science Fiction & Fantasy Speak, and have had reviews, interviews and articles appear in such venues as The Brutarian, Green Man Review and The Science Fiction Chronicle. My background's in journalism (big surprise, that) and for three years I served as the fiction editor over at RevolutionSF.

Thanks for stopping by to check out my obligatory "Who is this guy?" post here at No Fear of the Future. In case you're wondering (and I'll be deeply traumatized if you're not) I'm Jayme Lynn Blaschke, a science fiction and fantasy writer as well as journalist and PR flack from Texas. If you're a science fiction fan from the U.K., there's half a chance you may have heard of me, as Interzone has published more short fiction of mine than anyone else, not to mention a dozen or so interviews I've conducted with sage and knowing genre types over the years. If you're not British, then the pickin's get a bit leaner. I've published a collection of 17 interviews through Bison Books titled, Voices of Vision: Creators of Science Fiction & Fantasy Speak, and have had reviews, interviews and articles appear in such venues as The Brutarian, Green Man Review and The Science Fiction Chronicle. My background's in journalism (big surprise, that) and for three years I served as the fiction editor over at RevolutionSF.For those of you with a keen interest in such things, an original work of my short fiction, Coyote for President, is available over at RevSF, as is a reprint of another story of mine, Cyclops in B Minor. If you're more in the mood to read something printed on dead trees, you might check out Cross Plains Universe if you can track down a copy, which contains my story "Prince Koindrindra Escapes."

Finally, I have a somewhat spartan website at JaymeBlaschke.com and a slightly more entertaining blog titled Gibberish. What fix of me you don't get here you're liable to find there, in spades. Sorry this post is so dull and info-dumpy, but hey, it's a first post. I'll do better next time. Maybe.