Thursday, May 19, 2011

Scientific Process Rage

Paul Vallet created a hilarious and astute cartoon version of the scientific process as viewed by the general public and by scientists for the Electron Cafe. In the form of flow charts, it's a reaction to how the media tend to depict research as straightforward and rewarding. Vallet depicts the real deal as messily, maddeningly complicated and hard. Which it is. Scientists have been forwarding this to each other and getting a hearty laugh of self-recognition from it.

Monday, May 9, 2011

I was kidnapped by the Tijuana Liberation Front

[Vid: Kiosk dispensing sf minibuks to puzzled pedestrian border crossers.]

This past May Day weekend I had the good fortune to be a guest at one of the more interesting events I have ever attended: a science fictional convocation on the U.S.-Mexico border (like, so "on the border" the Homeland Security guys could watch our Power Point slides without the need to use the surveillance cameras looming over us). The event was "Lecturas de Cruce" (roughly, the "Crossing Lectures"), a four-day series of lectures, round tables, and performances endeavoring to illuminate the border region as a zone in which we can see and create the future. The lectures followed a two-month program of science fictional interventions, DESDE AQUI VE EL FUTURO (roughly, "from here you see the future"), in which students from the Autonomous University of Baja California under the tutelage of Professor (and science fiction writer) Pepe Rojo presented visions of the future to the travelers gathered at the border. The event was sponsored and programmed by the Tijuana Cultural Center (CECUT) under the direction and management of literary director Mara Maciel and her colleague Samantha Luna.

[Pic: Maestro Pepe Rojo, a little spent after the last evening of programming.]

The interventions included a talking dispensary of free science fiction books, a newspaper of the future handed out to the cars queued in the 90-minute line to cross, dance performances by pre-programmed cyborgs, future scenarios printed on bookmarks and handed out for consideration by the crowds, and even a procession of devotees of an imaginary saint, the cyborg Guadalupe known as Santa Ste.la, whose appearance with her acolytes passing through the center of Tijuana caused a near-riot, multiple anti-Satanic genuflections, and several calls for immediate baptisms.

[Pic: The procession of Sta.Ste.la.]

The idea of science fiction as the source of artistic interventions in real life is a brilliant and underused strategy. There are precedents—Ballard's 1960s crashed car installations, the recent post-apocalyptic reality show, and all our 20th century American Tomorrowlands—but no real direct analog (I can think of) for an event in which the imaginations of scores of local college students are harnessed to season the arteries of border commerce with visions of dozens of imminent futures. In the atemporal age of Network Culture ascendant, I expect and hope we will see more such speculative interventions in the present.

[Pic: Cyborg dancer points the way forward: through your head.]

The final event, the lecture program, was held in an abandoned government facility, a former Mexican passport office a couple of hundred yards from the U.S. border crossing. This is the chokepoint for the whole region, at which cars and pedestrian crossers converge to take their place in lines that can take hours, surrounded by dispensaries of prescriptionless pharmaceuticals (and soda bottles of pseudo-Viagra) and billboards advertising budget plastic surgery. During the program, stickers advised drivers to tune into the lectures on local simulcast as they sat in the adjacent lanes of crossing; they could even see the slides of the presenters as they approached. Overseeing it all was a giant Verizon billboard featuring an image that keynote presenter Bruce Sterling duly noted could have passed for an eyeball-kicking cyberpunk book cover in 1985, but is now taken for granted: a lovely woman surrounded in concentric colored halos of network radiance, begging Mexicans to plug into her 4G as fast as possible.

[Pic: A captive audience (programming underway to left of photo).]

In addition to Pepe and Bruce, participants included leading Mexican science fiction writers Bernardo Fernández (aka Bef), Gerardo Porcayo, Miguel Ángel Fernández, Gabriel Trujillo Muñoz, and children's author Francisco Hinojosa. Latin American sf scholar Professor Libby Ginway also attended and led most of the q&a. The program also included a screening of Alex Rivera's brilliant film Sleep Dealer, a cyberpunk tale of near-future Tijuana, and a performance of improvised techno by Casa Wagner (who also ended the program with a wild night of trance-inducing electrocumbia).

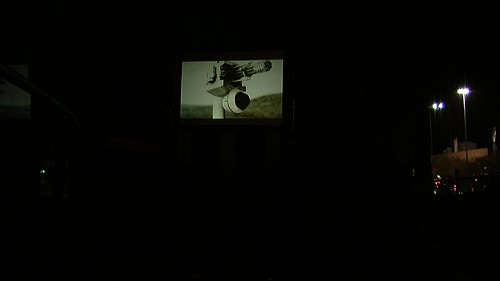

[Pic: Surveillance interrogation device presented by yours truly for the consideration of the captive audience.]

The border is a perfect place to go to envision futures. The border wall articulates an insanely dystopian present—a DMZ far more intimidating than the Berlin wall was for those of us saw it live and in the flesh complete with schefferhunds and land mines. Approaching Mexico from the US side, you are admonished with escalating warnings that you are, in essence, playing with your life by crossing over to Narcoland. For those of us who survived downtown Manhattan in the 70s and 80s, or DC in the early 90s, it's like back to the Escape From New York future. What you quickly realize after you have crossed over a few times is the extent to which the border is a permeable membrane designed to reinforce the fiction of political jurisdictional boundaries that Network Culture (including the culture of the most powerful network: Capital) is obliterating—and, as Berkeley's Wendy Brown suggests, the increasing effort to reinforce the border with physical and virtual fortifications is really just an effort by an increasingly irrelevant sovereign nation state to sustain the idea of its existence. Revealing an American future in which either the Nation State no longer exists in a form we recognize, or sustains the fiction of its 19th-20th century version through co-optation of a media-doped populace backed by a nascent Homeland Security sort of tyrannical force.

[Vid: Casa Wagner makes free jazz Tijuanense from the sonic materials of the border city.]

So while you think about what your own path would be to get Snake Plissken out of the cultural labyrinth, I would point you in the direction of Tijuana, where you can get some of the best Lacanian Cochinita Pibil around.

Thursday, May 5, 2011

All the sky... and I mean all of it

Now readers of Wired and Gizmodo may have already seen this (yeah, like we have such a huge crossover readership) but this is simply too spectacularly nifty not to share. The Photopic Sky Survey is something I would do if 1) I had a daring sense of adventure, 2) had an imagination large enough to conceive of such a project and 3) had astrophotography skills somewhat more accomplished than those of a nearsighted lemur. So what's the big deal? I'll let Nick Risinger explain:

In concrete terms, Risinger took a year to travel the globe, spending an inordinate amount of time in the western states of the U.S. and the western Cape of South Africa to effectively photograph the heavens visible from both the northern and southern hemispheres throughout the year. Encroaching light pollution has dramatically reduced the number of truly dark-sky sites on the Earth today, and Risinger had to travel quite a bit to reach these isolated areas. That's 45,000 miles by air, 12,000 overland. Any way you slice it, that's dedication. Click on the image above for a breathtaking tour of the largest true-color, all-sky photographic survey ever made.

The Photopic Sky Survey is a 5,000 megapixel photograph of the entire night sky stitched together from 37,440 exposures. Large in size and scope, it portrays a world far beyond the one beneath our feet and reveals our familiar Milky Way with unfamiliar clarity. When we look upon this image, we are in fact peering back in time, as much of the light—having traveled such vast distances—predates civilization itself.