Courtesy of Mike Holliday at the JGB list, the compete transcript of a 1979 Penthouse interview of J.G. Ballard by his friend Chris Evans. The interview is an outstandingly cogent and complete articulation of Ballard's key insights about man and technology, the essence of life in the 20th and 21st centuries, and the role of science fiction in understanding it all.

Penthouse 1979 (Vol.14 No.1) (U.K. edition)

PROFILE: J. G. BALLARD

THE SPACE AGE IS OVER

BY DR. CHRIS EVANS

Penthouse: Science fiction is supposed to reflect the future. How well

do you think it has done that over the years?

Ballard: I think it's been amazingly accurate, not necessarily in terms

of the technology itself, but in predicting society's response to

technology. Jules Verne, over 100 years ago, was the first writer of any

kind to respond to the impending transformation of society by

technology, and from his time onwards science fiction has picked out the

main preoccupations and anxieties of the Industrial Age, identifying

them way ahead of their appearance. Incidentally it has also anticipated

the present unease about science which has recently become a public

issue, but which was featured in SF as far back as the 1930s. I suspect

it will also turn out to have been extremely accurate in the way in

which it is now predicting or anticipating the peculiar affectless

quality of life in the 1980s and 90s.

Penthouse: What kind of things?

Ballard: Well, for example the way in which the traditional togetherness

of the village is giving way to the inbuilt loneliness of the new high

rises, or the peculiar fact that people nowadays like to be together not

in the old-fashioned way of, say, mingling on the piazza of an Italian

Renaissance city, but, instead, huddled together in traffic jams, bus

queues, on escalators and so on. It's a new kind of togetherness which

may seem totally alien, but it's the togetherness of modern technology,

and the science fiction writers of the 40s, 50s and 60s picked it out

unerringly as being a dominant feature of the future - often without

realising what they were doing.

Penthouse: Can you give an example?

Ballard: You've only got to look at copies of "Galaxy Magazine" and

"Astounding Science Fiction" of the early 50s to see the anxieties and

wish-fulfilment fantasies of modern surburbia and city life - the

escapist dreams of jet liners and airport lounges - all absolutely

contained in the science fiction of the period. Take Pohl and

Kornbluth's classic novel, "The Space Merchants". Here the future is

portrayed in terms of a world totally dominated by the advertising

agencies. It's a world run not by the Pentagon and the Kremlin but by

Madison Avenue, with giant rival advertising consortia fighting to

control everything and everyone through the mechanism of the mass media.

And indeed, we can look back now and realise that the logical evolution

of Western society of the 1950s would have been a world in which the

copywriter was king. It seems obvious in retrospect, but it took science

fiction writers to spot it and write about it a quarter of a century

ago.

Penthouse: You evidently don't rate too highly science fiction's highly

successful predictions about space travel?

Ballard: Well you can't underestimate that achievement, but in many ways

space travel was the least adventurous of all SF concepts. It so happens

that my first stories were being published at almost exactly the time

that Sputnik One - in case you've forgotten, that's the first artificial

satellite - was launched in 1957. At the time I remember a great mood of

optimism in science fiction circles. It seemed that the Sputniks had

ushered in the space age, and that everything that the science fiction

writers had been predicting for 100 years was coming true. And with the

space age, science fiction was set fair for a golden era. Now I

remember, paradoxically responding to this general euphoria, by being

intensely pessimistic rather than optimistic. Although I had no real

evidence to support my hunch - quite the opposite in fact - I felt very

strongly that the age of space, as far as science-fiction was concerned

was ending rather than beginning. And indeed the space age did end and

far from lasting hundreds or even thousands of years, its total life

span was hardly more than a decade. One can date its end quite

precisely. The space age clearly ended in 1974 when the last Skylab

mission came to earth. This was the first splashdown not to be shown on

TV - a highly significant decision on the part of the networks which

signalled the fact that space simply wasn't interesting any more. As I

said I had a strong hunch that this was the case, but didn't have any

unequivocal evidence to back it up. But in the summer of '74 I remember

standing out in my garden on a bright, clear night and watching a moving

dot of light in the sky which I realised was Skylab. I remember thinking

how fantastic it was that there were men up there, and I felt really

quite moved as I watched it. Through my mind there even flashed a line

from every Hollywood aviation movie of the 40s, "it takes guts to fly

those machines." But I meant it. Then my neighbour came out into his

garden to get something and I said, "Look, there's Skylab," and he

looked up and said, "Sky-what?" And I realised that he didn't know about

it, and he wasn't interested. No, from that moment there was no doubt in

my mind that the space age was over.

Penthouse: What is the explanation for this. Why are people so

indifferent?

Ballard: I think it's because we're at the climactic end of one huge age

of technology which began with the Industrial Revolution and which

lasted for about 200 years. We're also at the beginning of a second,

possibly even greater revolution, brought about by advances in computers

and by the development of information-processing devices of incredible

sophistication. It will be the era of artificial brains as opposed to

artificial muscles, and right now we stand at the midpoint between these

two huge epochs. Now it's my belief that people, unconsciously perhaps,

recognise this and also recognise that the space programme and the

conflict between NASA and the Soviet space effort belonged to the first

of these systems of technological exploration, and was therefore tied to

the past instead of the future. Don't misunderstand me - it was a

magnificent achievement to put a man on the moon, but it was essentially

nuts and bolts technology and therefore not qualitatively different from

the kind of engineering that built the Queen Mary or wrapped railroads

round the world in the 19th century. It was a technology that changed

peoples lives in all kinds of ways, and to a most dramatic extent, but

the space programme represented its fast guttering flicker.

Penthouse: You were one of the leaders of the "New Wave" in science

fiction. Could you say something about that? Was the New Wave a response

to the shift from one technological epoch to another?

Ballard: Yes, in a sense. You see technology advances on a number of

fronts and opens up a number of different doors. The transformation of

London by its tube system in the 19th century, the spread of the

telephone in the 1920s and 30s, the coming of radio and the dominance of

TV in the 50s and 60s were all tied up with technology, but with

communications and information transfer rather than with giant feats of

Meccano engineering. I was born in 1930, and I am old enough to remember

the popular encyclopaedias of the day, the mass magazines like "Life" in

which space exploration was seen as a natural extension of the

development of aviation. It took 50 years from the Wright Brothers to

the first faster than sound rocket planes in the '50s. It then seemed

only natural that the next step was Outer Space and these were the sort

of projections that "Old Wave" science fiction made about the future.

And while the logic of our past history seemed to be a continued

expansion outwards, a persistent invasion of extra-terrestrial

territory, the growth of communications technology in the 50s and 60s

was already suggesting that these huge spatial excursions were becoming

not only less and less necessary, but also less and less interesting.

The world of "Outer Space" which had hitherto been assumed to be

limitless was being revealed as essentially limited, a vast concourse of

essentially similar stars and planets whose exploration was likely to be

not only extremely difficult, but also perhaps intrinsically

disappointing. On the other hand, inside our heads so to speak, lay a

vast and genuinely infinite territory which, for the sake of contrast I

termed "Inner Space." The New Wave in science fiction - it's not a

phrase I care for actually - reflected this shift in priorities, from

Outer Space to Inner Space, and in my own writing I set out quite

deliberately to explore this terrain.

Penthouse: Was your novel "Crash" an investigation of Inner Space?

Ballard: Yes and no. "Crash" was really about the psychology of the

motor car, or about people's attitudes to the motor car, and it tried to

highlight the vast range of emotional ties that man has with this highly

specialised piece of technology. It was a kind of science fiction of the

present if you like. I'm not interested in motor cars myself by the way,

but I am interested in what motor cars say about modern man, and about

how they reflect man's needs and aspirations. Many people make the

mistake of assuming that people buy motor cars because of great

advertising and external social pressures. Nothing could be further from

the truth. Since the 1930s when styling first began to be a big feature

of design in the States, the automobile industry has emerged as a

perfect example of a huge technological system meeting profound

psychological needs. The motor car represents, and has done for 40

years, a very complex mesh of personal fulfilment of every conceivable

kind. On a superficial level it fulfills the need for a glamorous

package that is quite beautifully sculptured in steel and has all sorts

of built-in conceptual motifs. At a deeper level it represents the

dramatic role one can experience when in charge of a powerful machine

driving across the landscape of the world we live in, a role one can

share with the driver of an express train or the pilot of a 707. The

automobile also represents an extension of one's own personality in

numerous ways, offering an outlet for repressed sexuality and

aggression. Similarly it represents all kinds of positive freedoms - I

don't just mean freedom to move around from place to place, but freedoms

which we don't normally realise, or even accept we are interested in.

The freedom to kill oneself for example. When one is driving a car there

exists, on a second-by-second basis, the absolute freedom to involve

oneself in the most dramatic event of one's life, barring birth, which

is one's death. One could go on indefinitely pointing out how the motor

car is the one focus of so many currents of the era, and so many

conscious and unconscious pressures. Indeed if I had to pick a single

image which best represented the middle and late 20th century, it would

be that of a man sitting in a car, driving down a superhighway. "Crash"

was an attempt to explore this vast facet of human existence, and to

that extent, I suppose, was part of the exploration of Inner, as opposed

to Outer, space.

Penthouse: What was the general response to this shift of direction in

science fiction?

Ballard: Although initially it seemed as though the various "New Wave"

writers of the 60s were significantly off-beam because of the apparent

success of the space programme, I believe now that we were very much

more in tune with the public mood than perhaps we realised. Don't forget

that the 60s were the years of the resurgence in pop culture, and a

turning away from the external material culture of the early 20th

century. People no longer saw their lives in terms of establishing basic

material securities - I must have a job, I must have an apartment, cars,

washing machines. They all had jobs, apartments, cars and washing

machines.

What people wanted to gratify were psychological rather than material

needs. They wanted to get their sex lives right, their depressions

sorted out, they wanted to come to terms with psychological weaknesses

they had. And these were things that a materialistic society was unable

to supply - it couldn't wrap them up and sell them for a pound down and

ten pence a week. Now this rejection of external in favour of internal

values was mirrored in the great popular movements of the time. Take the

career of the Beatles who began in the traditional materialistic mould

of young Rock 'n Roll stars - flashy cars, expensive clothes, big

stadium concerts and all that but turned in the end towards meditation,

mysticism. the pseudo-philosophical drug culture of the psychedelics,

and so on. In other words there was a great current moving through

Western Europe and the USA in the 60s in a direction completely opposite

to that emanating from the Kennedy Space Centre The stars and the

planets were out, the bloodstream and the central nervous system were

in. It's no wonder that by the time Armstrong had put his foot on the

moon, no one was really interested.

Penthouse: Does that mean that the space programme has ended once and

for all. Are you saying that we'll never go any further?

Ballard: Oh, no, there'll be a space age some day, perhaps 30, 40 or

even 50 years from now, and when it comes it will be a real space age!

But it will depend upon the development of some new form of propulsion.

The main trouble with the present system - all these gigantic rockets

sailing up off the launch pads consuming tons of fuel for every foot of

altitude - is that it just hasn't got anything to do with space travel.

The number of astronauts who have gone into orbit after the expenditure

of this great ocean of rocket fuel is small to the point of being

ludicrous. And that sums it all up. You can't have a real space age from

which 99.999 per cent of the human race is excluded. Far more real - and

we don't have to wait 50 years for it - is the invisible space age which

exists already; the communications satellites, literally thousands of

them, television relay systems, spy satellites, weather satellites,

These are all changing our lives in a way that the average person

doesn't yet comprehend. The ability to pass information around from one

point in the globe to another in vast quantities and at stupendous

speeds, the ability to process information by fantastically powerful

computers, the intrusion of electronic data processing in whatever form

into all our lives is far, far more significant than all the rocket

launches, all the planetary probes, every footprint or tyre mark on the

lunar surface.

Penthouse: How do you see the future developing?

Ballard: I see the future developing in just one way - towards the home.

In fact I would say that if one had to categorise the future in one

word, it would be that word "home." Just as the 20th century has been

the age of mobility, largely through the motor car, so the next era will

be one in which instead of having to seek out one's adventures through

travel, one creates them, in whatever form one chooses, in one's home.

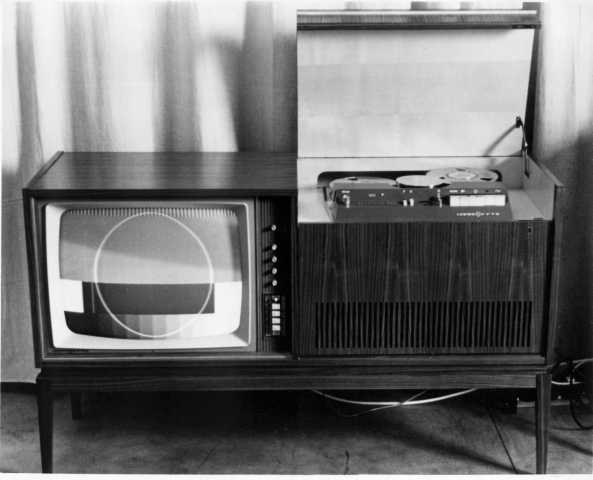

The average individual won't just have a tape recorder, a stereo HiFi,

or a TV set. He'll have all the resources of a modern TV studio at his

fingertips, coupled with data processing devices of incredible

sophistication and power. No longer will he have to accept the

relatively small number of permutations of fantasy that the movie and TV

companies serve up to him, but he will be able to generate whatever he

pleases to suit his whim. In this way people will soon realise that they

can maximise the future of their lives with new realms of social, sexual

and personal relationships, all waiting to be experienced in terms of

these electronic systems, and all this exploration will take place in

their living rooms.

But there's more to it than that. For the first time it will become

truly possible to explore extensively and in depth the psychopathology

of one's own life without any fear of moral condemnation. Although we've

seen a collapse of many taboos within the last decade or so, there are

still aspects of existence which are not counted as being legitimate to

explore or experience mainly because of their deleterious or irritating

effects on other people. Now I'm not talking about criminally

psychopathic acts, but what I would consider as the more traditional

psychopathic deviancies. Many, perhaps most of these, need to be

expressed in concrete forms, and their expression at present gets people

into trouble. One can think of a million examples, but if your deviant

impulses push you in the direction of molesting old ladies, or cutting

girl's pig tails off in bus queues, then, quite rightly, you find

yourself in the local magistrates court if you succumb to them. And the

reason for this is that you're intruding on other people's life space.

But with the new multi-media potential of your own computerised TV

studio, where limitless simulations can be played out in totally

convincing style, one will be able to explore, in a wholly benign and

harmless way, every type of impulse - impulses so deviant that they

might have seemed, say to our parents, to be completely corrupt and

degenerate.

Penthouse: Can you be sure that their exploration, even if they don't

involve other people in the "real sense," will be purely benign?

Ballard: Well it seems to me that these kinds of explorations have been

going on, if only in a limited sense, since time immemorial. Take the

whole business of organised sports and games which have been a major

preoccupation of man for tens of thousands of years. Now there's no

point in pretending that these games are played and watched solely

because of the fact that they determine some trial of skill or bravery

between opposing teams. The exhilaration of sport, from the pumping of

one's lungs, the twisting of ankles, the bruising of the rugger field,

the physical damage of the boxing match, and right at the other end of

the scale the multiple deaths of a Formula Two pile-up are all major

components, and all might seem like totally deviant pleasures if they

were not long-established components of participant and spectator

sports. Even today the idea that people watching a car race get some

measure of excitement from being an observer of an accident which

produces pain, mutilation and death, is somehow slightly shocking and

yet it's clearly one of the reasons why people go to motor races. But I

think we'll shortly be moving into a realm where we will be prepared to

take for granted the existence of these seemingly deviant interests and

through the limitless powers of our home computers and TV we will be

granted universes of experience which today seem to belong to the dark

side of so-called civilised behaviour. Of course this doesn't apply

solely to sport or to activities like the space programme; with the kind

of simulations I'm envisaging it may never be necessary to go into

space. One's own drawing room will be a thousand times more exciting

and, in a peculiar way, more "real." No, there will be a huge range of

activities, our sex lives included, in which we can explore endlessly

the permutations of possible relationships with our friends, wives,

lovers, husbands, in a completely uninhibited way, but also in a way

which is neither physically hurtful nor psychologically or morally

corrupting.

Penthouse: Will people really respond to these creative possibilities

themselves? Won't the creation of these scenarios always be handed over

to the expert or professional?

Ballard: I doubt it. The experts or professionals only handle these

tools when they are too expensive or too complex for the average person

to manage them. As soon as the technology becomes cheap and simple,

ordinary people get to work with it. One's only got to think of people's

human responses to a new device like the camera. If you go back 30 or 40

years the Baby Brownie gave our parents a completely new window on the

world. They could actually go into the garden and take a photograph of

you tottering around on the lawn, take it down to the chemists, and then

actually see their small child falling into the garden pool whenever and

as often as they wanted to. I well remember my own parents' excitement

and satisfaction when looking at these blurry pictures, which

represented only the simplest replay of the most totally commonplace.

And indeed there's an interesting point here. Far from being applied to

mammoth productions in the form of personal space adventures, or one's

own participation in a death-defying race at Brands Hatch it's my view

that the incredibly sophisticated hook-ups of TV cameras and computers

which we will all have at our fingertips tomorrow will most frequently

be applied to the supremely ordinary, the absolutely commonplace. I can

visualise for example a world ten years from now where every activity of

one's life will be constantly recorded by multiple computer-controlled

TV cameras throughout the day so that when the evening comes instead of

having to watch the news as transmitted by BBC or ITV - that irrelevant

mixture of information about a largely fictional external world - one

will be able to sit down, relax and watch the real news. And the real

news of course will be a computer-selected and computer-edited version

of the days rushes. "My God, there's Jenny having her first ice cream!"

or "There's Candy coming home from school with her new friend." Now all

that may seem madly mundane, but, as I said, it will be the real news of

the day, as and how it affects every individual. Anyone in doubt about

the compulsion of this kind of thing just has to think for a moment of

how much is conveyed in a simple family snapshot, and of how rivetingly

interesting - to oneself and family only of course - are even the

simplest of holiday home movies today. Now extend your mind to the

fantastic visual experience which tomorrow's camera and editing

facilities will allow. And I am not just thinking about sex, although

once the colour 3-D cameras move into the bedroom the possibilities are

limitless and open to anyone's imagination. But let's take another

level, as yet more or less totally unexplored by cameras, still or

movie, such as a parent's love for one's very young children. That

wonderful intimacy that comes on every conceivable level - the warmth

and rapport you have with a two-year-old infant, the close physical

contact, his pleasure in fiddling with your tie, your curious

satisfaction when he dribbles all over you, all these things which make

up the indefinable joys of parenthood. Now imagine these being viewed

and recorded by a very discriminating TV camera, programmed at the end

of the day, or at the end of the year, or at the end of the decade, to

make the optimum selection of images designed to give you a sense of the

absolute and enduring reality of your own experience. With such

technology interfaced with immensely intelligent computers I think we

may genuinely be able to transcend time. One will be able to indulge

oneself in a kind of continuing imagery which, for the first time will

allow us to dominate the awful finiteness of life. Great portions of our

waking state will be spent in a constant mood of self-awareness and

excitement, endlessly replaying the simplest basic life experiences.

Penthouse: But isn't this tremendously passive?

Ballard: Just the opposite. I would say we were moving towards an era

where the brain with its tremendous sensory, aesthetic and emotional

possibilities will be switched on, totally instead of partially, for the

very first time. The enormously detailed, meticulously chosen re-runs I

have been talking about will give one a new awareness of the wonder and

mystery of life, an awareness that most of us, for biologically

important reasons have been trained to exclude. Don't forget that man

is, and has been for at least a million years, a hunting species

surviving with difficulty in a terribly dangerous world. In order to

survive, his brain has been trained to screen out anything but the most

essential and the most critical. Watch that hillcrest! Beware of that

cave mouth! Kill that bird! Dodge that spear! And in doing so he has to

screen out all the penumbral wonder of existence. But now the world is

essentially far less dangerous, and the time has come where the brain

can be allowed to experience the true excitement of the universe, and

the infinite possibilities of consciousness that the basic needs of

survival have previously screened away. After a million or so years,

those screens are about to be removed and once they have gone, then, for

the first time, man will really know what it is to be alive.

For a fresher dose, check out this German interview at Ballardian, "I really would not want to fuck George W. Bush."

No comments:

Post a Comment