Looking for some invisible literature to enjoy over the long weekend? A clinically rigorous, heartless prose dissecting some weird corner of reality, perfect antidote to whatever piles of literary ink on paper you found under your tree? You are in luck: NASA has just released the Columbia Crew Survival Investigation Report, 400 pages of the most detailed description of astronautical death imaginable (except, maybe, for the unredacted version of what was released to the public). As if the opening credits of The Six Million Dollar Man ("She's breaking up!") were rewritten in the style of The Atrocity Exhibition. Even better, it's a *speculative* narrative, extrapolating from the insane quantities of evidence each of the "events of lethal potential" that may have been the point at which one or more of the astronauts died:

1. Depressurization of the crew module as the orbiter began breakup, when most of the astronauts had their helmet visors up and some did not have their gloves on. The report suggests the entire crew was killed or rendered unconscious at this point, but it also reads like they want that to be the case because the idea of death at any of the subsequent points is so horrific.

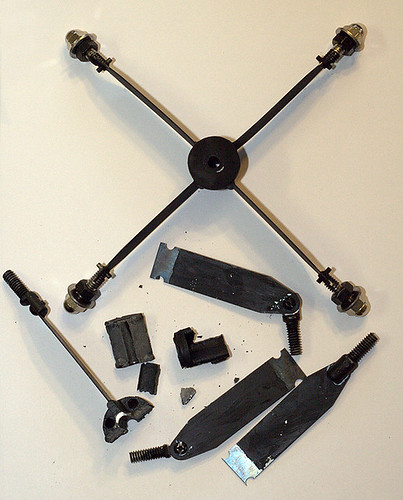

2. Exposure "to a dynamic rotating load environment with nonconformal helmets and a lack of upper body restraint" — heads being slammed against the insides of helmets that were not padded for such purposes, and torsos being whiplashed without shoulder belts, as the crew module windmilled through the high atmosphere.

3. The seats being torn from the module, and the crew members being torn loose from the seats.

4. "[E]xposure to near vacuum, aerodynamic accelerations, and cold temperatures" somewhere above 63,000 feet.

5. Ground impact.

The express purpose of the report is to aid future spacecraft designers and accident investigators, while the obvious unspoken purpose is to support a desired view that no astronaut experienced prolonged suffering. The methodology is the application of the most advanced air crash investigative techniques to support a detailed timeline, a comprehensive "vehicle failure assessment," and a thorough if sanitized review of each aspect of the "occupant protection" — seats, restraints, shuttle suits, helmets, training, etc. The level of detail is seriously mind-boggling, with detailed charts and analyses of each individual piece of shuttle material recovered, astronaut suit fragment, frayed seat restraint, and maps of debris distribution from Plano to Nacogdoches.

Some representative excerpts:

3.4.2 Injury classifications

3.4.2.1 Exposure to high altitude

[REDACTED.] Given the level of tissue damage, the crew could not have regained consciousness even with re-pressurization. Survival was possible, but not likely, even with immediate and extensive medical intervention at this point. Although respiration would cease after depressurization, circulatory functions can exist for a short period of time.

[REDACTED.]

Finding. Tissue samples revealed evidence of ebullism.

Conclusion L1-3. The crew was exposed to a pressure altitude above 63,500 feet, indicating that the cabin depressurization event occurred above this altitude.

[REDACTED.]

Finding. The depressurization event occurred prior to the loss of circulatory function.

There is very limited data on human exposure to space-equivalent vacuum. [REDACTED.] Although the Soyuz 11 cabin depressurization was relatively slow (reportedly taking more than 3.5 minutes to depressurize to 0 psi), it was stated that the depressurization was fatal to the crew in roughly 30 seconds.12 Because the exact scenario cannot be positively identified, no conclusions with respect to the rate or timing of cabin depressurization can be made from the medical findings.

[REDACTED.]

Depressurization events in aviation have led to extensive studies on “time of useful consciousness (TUC).” TUC is generally based on the remaining amount of O2 in the tissues that is permitting brain functions to continue. Various factors affect the TUC (i.e., exertion, depressurization rate, pre-exposure O2 partial pressure, G-loads, adrenaline loading, etc.). Since the shuttle cabin uses air, the pre-exposure O2 partial pressure was only 21% O2 (the normal for sea-level). Based on debris and structural evidence, the most likely time for the initiation of cabin depressurization was at orbiter breakup (CE) at GMT 14:00:18.

Based on video evidence, the depressurization was complete no later than GMT 14:00:59 (figure 3.4-15), and likely much earlier (see Section 2.3). This corresponded to an altitude range of 181,000 feet to approximately 140,000 feet. Traditional aviation TUC would correlate a rapid depressurization at these altitudes to a TUC of 12 seconds. This would have been enough time for the crew to close their visors and initiate O2 flow, and yet they did not (see Section 3.2).

However, additional research discussed in Joint Aerospace Physiology, Air Education and Training Command/Bureau of Medicine and Surgery shows that the physiological response to hypoxia during a rapid depressurization event at this extreme altitude (181,000 feet) would have reduced the conventional TUC interval by 50% (i.e., 12 seconds would have been reduced to 6 seconds). In addition to the depressurization effects, the physical exertion against the G-forces that the crew experienced at this time would further reduce the available metabolic O2 reserves and increase the CO2 partial pressure. Also, NASA research data indicate that de-conditioned crews have a reduced tolerance to G-loads. Further, anecdotal reports from accidental exposure to vacuum confirm much shorter periods of awareness as reported by survivors.

The 51-L Challenger accident investigation showed that the Challenger CM remained intact and the crew was able to take some immediate actions after vehicle breakup, although the accelerations experienced were much higher as a result of the aerodynamic loads (estimated at G to 21 G). The Challenger crew became incapacitated quickly and could not complete activation of all breathing air systems, leading to the conclusion that an incapacitating cabin depressurization occurred. By comparison, the Columbia crew experienced lower loads (~3.5 G) at the CE. The fact that none of the crew members lowered their visors strongly suggests that the crew was incapacitated after the CE by a rapid depressurization.

From this time forward, the crew members would have been unconscious, totally unaware of events, and unable to brace against the loads. With the configuration of the ACES (i.e., visors up and three crew members without gloves donned), the depressurization was an event of lethal potential. Had the ACES been configured with the visors down and locked, gloves on, and EOS activated, the depressurization event by itself probably would have been survivable.

Finding. No conclusion could be drawn as to the rate of cabin depressurization based on medical evidence.

Finding. None of the six crew members wearing helmets closed their visors.

Conclusion L1-5. The depressurization incapacitated the crew members so rapidly that they were not able to lower their helmet visors.

Recommendation L1-3/L5-1. Future spacecraft crew survival systems should not rely on manual activation to protect the crew.

Conclusion A8-1. Spacecraft accidents are rare, and each event adds critical knowledge and understanding to the database of experience.

Recommendation A8. As was executed with Columbia, spacecraft accident investigation plans must include provisions for debris and data preservation and security. All debris and data should be cataloged, stored, and preserved so they will be available for future investigations or studies.

3.4.2.2 Mechanical injuries

Mechanical injuries were isolated to the period of time at which they most likely occurred, based on engineering analyses of motions and accelerations.

Pre-Catastrophic Event

[REDACTED.]

Catastrophic Event to Crew Module Catastrophic Event

A very dynamic motion environment existed after the CE (GMT 14:00:18); this environment became more intense as the CMCE (the breakup of the forebody) approached at GMT 14:00:53. Figure 3.4-16 shows representative loads on the unconscious or deceased crew members based on aerodynamic modeling of the forebody dynamics post-CE. The black dashed lines showing human performance limits20 are for conscious crew members. Based on the conclusion that the rapid depressurization occurred at or close to the time of the orbiter forebody separation, the crew was unconscious or deceased and unable to brace against these loads.

For the first 15 to 20 seconds, the modeled loads would not cause serious injuries to a conscious crew member who was capable of active bracing. An unconscious or deceased crew member would have been more susceptible to injury.

The crew is normally restrained in the seats by a five-point harness system (figure 3.4-17). A lap belt secures the lower torso. A crotch strap prevents “submarining.”21 Two shoulder harnesses, which attach to an inertial reel via the inertial reel strap, secure the upper torso.

Engineering analysis of the STS-107 restraints indicates that most of the inertial reel straps were extended and did not lock or retract prior to failure of the straps. The inertial reels are normally unlocked to allow the crew to access displays and controls with a full range of motion. With the inertial reels unlocked, the crew members’ upper bodies were left unrestrained during the forebody dynamics. [REDACTED.]

Finding. One crew member appears to have been restrained only by the shoulder harness and crotch strap.

Recommendation L1-2. Future spacecraft and crew survival systems should be designed such that the equipment and procedures provided to protect the crew in emergency situations are compatible with nominal operations. Future spacecraft vehicles, equipment, and mission timelines should be designed such that a suited crew member can perform all operations without compromising the configuration of the survival suit during critical phases of flight.

[REDACTED.]

Figure 3.4-18 provides a demonstration of an integrated seat/suit/crew member in entry configuration.

[REDACTED.] Figure 3.4-19 shows an interior view of an intact, pristine ACES helmet demonstrating exposed hardware. [REDACTED.]

[REDACTED. Figure 3.4-20.]

Finding. Injuries were consistent with the crew’s upper bodies not being securely held to the seatbacks and with the evidence indicating that the inertial reel straps were extended at the time of failure.

Finding. Injuries were consistent with the crew’s upper bodies not being supported during the time of dynamic motion.

Conclusion L2-3. Lethal injuries resulted from inadequate upper body restraint and protection during rotational motion.

Recommendation L2-4/L3-4. Future spacecraft suits and seat restraints should use state-of-the-art technology in an integrated solution to minimize crew injury and maximize crew survival in off-nominal acceleration environments.

Recommendation L2-7. Design suit helmets with head protection as a functional requirement, not just as a portion of the pressure garment. Suits should incorporate conformal helmets with head and neck restraint devices, similar to helmet/head restraint techniques used in professional automobile racing.

Recommendation L2-8. The current shuttle inertial reels should be manually locked at the first sign of an off-nominal situation.

Recommendation L2-9. The use of inertial reels in future restraint systems should be evaluated to ensure that they are capable of protecting the crew during nominal and off-nominal situations without active crew intervention.

Crew Module Catastrophic Event

[REDACTED.] Engineering and ballistic analyses of the orbiter forebody failure indicate that the middeck separated prior to the flight deck. Crew members on the middeck separated along with the middeck accommodations rack, middeck lockers, sub-floor components, and Modular Auxiliary Data System/orbiter experiment data recorder – a scenario that is supported by debris plots (see Section 2.2). Based on structural design analysis, thermal damage, and position in the debris field, the flight deck “pod” and the CM aft bulkhead stayed intact for a longer time. The location of the recovered flight crew equipment, which is plotted in figure 3.4-21, supports the middeck departing prior to the flight deck.

[REDACTED.]

[REDACTED. Figure 3.4-22.]

[REDACTED.]

Finding. Crew members experienced traumatic injuries in areas corresponding to the seat restraint system.

Conclusion L3-4. The seat restraint system caused lethal-level injuries to the unconscious or deceased crew members when they separated from the seat.

Recommendation L2-4/L3-4. Future spacecraft suits and seat restraints should use state-of-the-art technology in an integrated solution to minimize crew injury and maximize crew survival in off-nominal acceleration environments.

Recommendation L3-1. Future vehicles should incorporate a design analysis for breakup to help guide design toward the most graceful degradation of the integrated vehicle systems and structure to maximize crew survival.

3.4.2.3 Thermal exposure

[REDACTED.]

Finding. No significant levels of carbon monoxide or cyanide (combustion by-products) were identified in any of the body fluids.

Finding. There was no evidence of thermal injury to the respiratory tracts.

Conclusion L1-4. The crew was not exposed to a cabin fire or thermal injury prior to depressurization, cessation of breathing, and loss of consciousness.

[REDACTED.]

[REDACTED. Figure 3.4-23.]

[REDACTED.]

The ambient absolute pressure condition at separation was approximately 0.03 psi.

3.4.3 Identified events with lethal potential

1. The first event with lethal potential was depressurization of the CM, which started at or shortly after orbiter breakup. Existing crew equipment protects for this type of lethal event, but operational practices and hardware limitations were such that the ACESs were not in a protective configuration. The current shuttle ACES relies on the crew to lower and lock the visor; therefore, complete protection from a depressurization event depends on a permissive environment. Design solutions that do not require crew action are achievable.

2. The second event with lethal potential was unconscious or deceased crew members exposed to a dynamic rotating load environment with nonconformal helmets and a lack of upper body restraint. Current shuttle seat and helmet design and operational practices did not protect the crew members from this lethal event. Complete strap-in with inertial reels locked would reduce the risk of injury/death; however, even in this configuration, the current seat-suit restraint system provides limited protection from dynamic G events (i.e., no lateral restraints, no control of extremity motion, and no head-neck support). Better restraint designs that include head-neck support (i.e., conformal helmets), extremity control, and spine support are achievable to reduce the risk of injury/death.

3. The third event with lethal potential was separation from the crew module and the seats with associated forces, material interactions, and thermal consequences. This event is the least understood due to limitations in current knowledge of mechanisms at this Mach number and altitude. Seat restraints played a role in the lethality of this event. Although the seat restraints (e.g., narrow width) played a significant role in the lethal mechanical injuries, there is currently no full range of equipment to protect for this event. The event was not survivable by any means currently known to the investigative team, with the exception of ensuring the integrity of the CM until the airspeed and altitude are within survival limits. This is not possible for the current space shuttle design; however, future vehicle designs incorporating a principle of “graceful degradation” and CM stabilization are possible.

4. The fourth event with lethal potential was exposure to near vacuum, aerodynamic accelerations, and cold temperatures. Although current crew survival equipment may be capable of protecting the crew, it is not certified to protect the crew above 100,000 feet. At the altitude and speeds at which the unconscious or deceased crew members departed from the CM, the environmental risks include lack of O2, low atmospheric pressure, high thermal loads as a result of deceleration from high Mach numbers, shock wave interactions, aerodynamic accelerations, and exposure to cold temperatures. Existing shuttle CEE is certified to protect up to 100,000 feet and 600 KEAS; however, the ACES is not designed to provide protection from high-temperature exposures. Anecdotal evidence from the survival of the pilot of an SR-71 mishap [Aviation Week & Space Technology, August 8, 2005, pp. 60–62] suggests that an intact, pressurized suit similar to the ACES can protect a crew member at an altitude of 78,000 feet and speeds of at least Mach 3 (~400 KEAS). More research is needed to close the survival gap. The only protection that is achievable is to ensure the integrity of the CM until the airspeed and altitude are within suit capability, which is currently not precisely determined.

5. The final event with lethal potential was ground impact. Existing shuttle CEE protects for ground impact with a parachute. However, the crew member must manually initiate the parachute opening sequence, or the parachute must be used in conjunction with the crew escape pole of the shuttle to initiate the parachute automatic opening sequence. Military and sport parachuting solutions exist for opening parachutes independent of crew action.

3.4.4 Synopsis of crew analysis

The crew was unaware of an impending survival situation prior to the LOC. At the time of LOC, the flight deck crew was probably troubleshooting the caution-and-warning messages that were associated with the FCS fault, left main landing gear talk-back, and tire pressure messages. One of the middeck crew members was likely attempting to become seated and restrained under the dynamic LOC conditions. Until the forebody separated from the orbiter vehicle, the crew was conscious and had not suffered serious injuries. Cause of death was unprotected exposure to high-altitude conditions and blunt trauma.

[REDACTED.]

If you're skeptical about the likelihood of being able to actually increase the chances of astronauts surviving the break-up of the spacecraft during re-entry, consider the following discussion, with particular reference to the SR-71 comparison:

3.2.2 Crew worn equipment configuration

Recovered videotape from Columbia revealed information related to the configuration of the crew worn survival equipment, including the helmets and the ACESs. The recovered middeck video shows the seat 5 crew member suited (except for the helmet and gloves) and the seat 1 and seat 6 crew members donning their suits. The middeck video, which does not include views of other flight deck crew members donning their suits, ends prior to the seat 7 crew member donning the ACES.

Recovered flight deck video shows the flight deck crew members suited with helmets and gloves on (except one crew member, who had not completed donning gloves by the end of the video). This video also shows the helmet and helmet neck rings in close proximity to the crew members’ chins. Because the helmets appeared to be restrained, investigators concluded that the crew members had the proper tension on the neck ring tie-down straps.

Although all crew members were wearing the main portion of the suit at the time of the accident, at some point the suits completely failed and separated. The SCSIIT investigated similar cases to understand the mechanism of suit failure.

3.2.3 Aircraft in-flight breakup case studies

The following civil aviation accidents provide examples of cases of passenger clothing being shed (body denuding) during in-flight breakups:

• Air India Flight 182 was flying at 31,000 feet over the Atlantic Ocean on June 23, 1985 when a terrorist bomb exploded in the baggage compartment. The Boeing 747 aircraft broke up in flight, and at least 21 of the 131 recovered bodies were denuded.

• Iran Air Flight 655 was mistakenly shot down by a U.S. Navy ship on July 3, 1988 while flying over the Persian Gulf. After missiles hit it, the Airbus A300 aircraft broke up in flight at an altitude of 13,500 feet. The denuded bodies of the passengers

were recovered from the Persian Gulf waters.

• Pan Am Flight 103 was blown up by a terrorist bomb over Lockerbie, Scotland on December 21, 1988. The bomb went off when the Boeing 747 aircraft was at roughly 31,000 feet and 313 knots airspeed; numerous passengers who had separated from the aircraft prior to ground impact were denuded.

• COPA Flight 201 broke up over the jungle in Panama on June 6, 1992. The Boeing 737 aircraft broke up at approximately 13,000 feet while in a high-speed dive (the pilots entered the dive because of a faulty attitude indication that was due to a wiring problem). Many of the passengers’ bodies were denuded.

These aviation accidents involved lower altitudes and slower speeds than those associated with the Columbia accident. However, a military accident more similar to the Columbia accident occurred on January 25, 1966 involving an SR-71 test flight. The pilot lost control of the aircraft, and the SR-71 broke up while flying at approximately Mach 3 at over 75,000 feet (~400 knots equivalent airspeed (KEAS)). The pilot survived, but the reconnaissance systems officer was killed. Points of similarity to the Columbia accident include:

• The SR-71 accident occurred at high speed and relatively high altitude.

• The SR-71 aircraft breakup dynamics resulted in a fatality.

• The SR-71 aircraft breakup dynamics included crew member separation from the vehicle.

• The seat restraint straps failed.

• The SR-71 pressure suit is very similar to the shuttle ACES in design and construction.

• The dynamic pressure at the Columbia CMCE was roughly 405 pounds per square foot (psf) and the dynamic pressure at SR-71 aircraft breakup was roughly 398 psf, a difference of less than 2%.

However, there are also notable differences between the two accidents. These include:

• The SR-71 pilot’s suit pressurized automatically (as designed) when the cockpit depressurized due to the aircraft breakup. The pilot attributed his survival to the pressurized suit, which protected him from the low-pressure/low-O2 environment as well as the aerodynamic forces (windblast) that he experienced when he separated from the aircraft. As discussed in the sections below, the Columbia suits did not pressurize because the crew members did not lower visors or activate the suit O2 system. Additionally, three crew members did not complete donning gloves, which is required for the suit to pressurize.

• While the Columbia crew members were exposed to a similar dynamic pressure environment as the SR-71 crew members, the thermal environment of the Columbia accident was much more severe than that experienced during the SR-71 breakup.

• Because of the altitude differences, the chemical environment (higher concentration of more reactive monatomic oxygen) of the Columbia accident differs from that of the SR-71 breakup.

• The Columbia suits did not remain intact, whereas the SR-71 pressure suits did remain intact.

Aerodynamic analysis indicates that the equivalent airspeed of the CM at the CMCE (GMT 14:00:53) was roughly 400 KEAS, and that it increased to 560 KEAS by the time of Total Dispersal (TD) (GMT 14:01:10). The ACES is designed to maintain structural integrity and pressure response capability when exposed to at least a 560-KEAS windblast. Since the suit is certified by NASA to meet this requirement based on its similarity to the pressure suit used by the U.S. Air Force, it was not subjected to windblast tests for certification. By contrast, the U.S. Air Force suit was tested in a certification program in 1990 during which it was exposed to a 600-KEAS windblast (the suit was worn by a manikin that was restrained in an ejection seat with the helmet visor down and locked). During the first test (suit not pressurized), the helmet sun shield separated from the helmet and a life preserver unit inflation tube separated from the life preserver unit. During the second test (the suit was pressurized to 2.99 psi), both shin pockets (survival gear storage pockets) were forced open. No other relevant anomalies were observed.

In the U.S. Air Force windblast test configuration, the helmet visors were lowered, which is notably different from the position of the Columbia visors. Debris evidence indicates that the Columbia helmet visors were up. With the helmet visor up, the helmet cavity presents a high drag configuration that could contribute to a mechanical failure of the suit/helmet interface, leading to suit disruption.

Standard materials testing data exist for the suit materials (GORE-TEX®, Nomex, nylon, etc.). However, the data are for tests conducted at “normal” environmental conditions (sea-level atmospheric temperature, pressure, and composition). Little laboratory test data exist on the performance of the materials in extreme environments. The lack of laboratory data presents an information gap regarding how the materials properties of the ACES are affected by exposure to the thermal and chemical environments at the altitudes and speeds experienced by Columbia. Although the more severe thermal and chemical environment of the Columbia accident may have weakened the suit materials, hastening suit disruption, the extent to which the thermal/chemical environment contributed to suit disruption cannot be determined from the debris and because the environment’s affects on suit materials is not understood.

Complete report (PDF).

Previous posts regarding invisible literature, including "The Assassination Inquest of Diana, Princess of Wales Considered as an Unintentionally Ballardian Remix of the Warren Commission Report."